Grammar

Homework Help & Tutoring

We offer an array of different online Grammar tutors, all of whom are advanced in their fields and highly qualified to instruct you.

Grammar

Language changes; it always has and always will. It evolves and adapts to the needs of its users, who all bring their own influences to bear on it. You might think of language as a river with many tributaries flowing into it. Into the source of the river of the English language has flowed Greek, Latin and Germanic languages. In 1066, the Normans added French, then with the European Renaissance more Latin and Greek trickled into the river, with later, smaller tributaries adding more diverse influences.

Queen Elizabeth I introduced us to ‘correct’ English in 1592, and even today we still often call it the Queen’s English – along with conventional, standard, pure, Oxford or BBC English. Formal English relates not only to accent and pronunciation, but to correct grammar usage and word choice (and in the written word, also to spelling and punctuation). Whilst there are several obvious differences between American and British English, the grammatical rules, for the most part, are the same. At 24HourAnswers, we recognize the importance of using grammar correctly in your speech and your written subjects, and we have a team of experienced writing tutors ready to help with your written assignments and your grammar needs.

It is easy to dismiss rigid rules of grammar as stuffy and old fashioned, but it is a sad fact that one third of all graduate job applications (even from graduates with good degrees from the top universities) are rejected because of sloppy English usage, and in particular poor grammar (www.independent.co.uk)

Why have we become so lazy about our language? The theories are too numerous to list here, and matter little, since what concerns us in these pages is to highlight some of the more common grammatical errors we make in everyday speech and writing, and explain how to rectify these.

I hope students will find these pages helpful. For more self-check exercises, students might find www.grammarbank.com or www2.ing.unipi.it/scuola_dottorato_ingegneria to be useful resources.

Apostrophes

There are two types of apostrophes – the first denoting abbreviations and the second denoting possession.

Abbreviations

These apostrophes take the place of missing letter(s) and make writing informal.

E.g.

I can’t do that (informal)

= I cannot do that (formal)

He’s gone home (informal)

= He has gone home (formal)

Those are the easy apostrophes.

It doesn’t matter how many letters need replacing – you only need one apostrophe in place of them.

E.g.

He’d have done his homework if he could.

= He would have done his homework...

(but avoid ‘He would’ve done it’ – as this sounds clumsy)

Possession

Possessive apostrophes show ownership.

Matthew’s coat was on the floor.

A golden rule for this type of apostrophe is to ask yourself who is doing the owning?

e.g. Matthew owns the coat. Therefore, place the apostrophe after Matthew.

Here’s another example:

The children’s books were on their desks.

(who owned the books?) The children own the books – therefore, place the apostrophe after children (because the word is already in its plural form)

Possession of plurals

Many plural words end in ‘s’. Here’s how the apostrophe works in those cases.

The teachers’ meeting was held in the library.

(Whose meeting? The teachers. Therefore the apostrophe goes after the word teachers)

Never use an apostrophe just to show plurality – e.g. snack’s (incorrect).

Hence:

The youths disturbed a wasps’ nest.

The workmen’s tools were in the shed.

The farmers’ market is held every weekend.

My best friend’s sister is called Jenny.

The spiders’ webs glistened in the morning sun.

The girls’ books were stacked neatly.

Colons and Semi-Colons

A colon is used to introduce a list.

E.g.

On your resume, you will need to include the following information: name, address, telephone number.

A semi-colon is used to create a pause, and fits somewhere between a comma and a full stop. It makes a connection between two independent but closely related clauses.

E.g.

Sarah loves cooking; her speciality is Mexican cuisine.

Such clauses can also be connected by a comma plus a co-ordinating conjunction* (but, and, or etc.)

E.g.

Sarah loves cooking, and her speciality is Mexican cuisine.

Semi-colons can also be used to separate longer items in a list that already contains a number of commas.

E.g.

To make the recipe you will need six boneless chicken thighs, cut into quarters; three large, flat mushrooms, cleaned and sliced; one medium onion, peeled and finely chopped; three tomatoes, peeled, deseeded and cut into quarters; one egg, lightly beaten, and one small glass of dry white wine.

Commas

Comma Splicing

Comma splicing means separating two or more sentences with a comma instead of a period or semicolon. It often occurs when writers use transitional words like therefore, however, nevertheless, furthermore, or moreover.

E.g.

His aim was to win the race, however, he tripped over at the last hurdle. (incorrect)

His aim was to win the race; however, he tripped over at the last hurdle. (correct)

And

My friends and I love to dance until late on Saturdays, we can rest all day Sunday. (incorrect)

My friends and I love to dance until late on Saturdays. We can rest all day Sunday. (correct)

Never try to merge two independent clauses simply by using a comma. Each of the two clauses in the above examples represents a complete sentence. A sentence expresses a complete thought and needs something more powerful than a comma at the end. Using a comma creates a run-on sentence, which readers find annoying.

Make sure you understand the difference between dependent and independent clauses. A dependent clause cannot be a full sentence, because it does not express a complete thought.

E.g.

Because I went to bed early

Although I did well in my exams

The above examples leave you wondering what happened next and, therefore, cannot stand alone as sentences.

An independent clause can act as a full sentence:

E.g.

Sarah does not like coffee.

Thomas almost missed his train.

There are several ways of repairing comma splices, or run-on sentences; the simplest being to make sure each clause is a complete thought and separate each with a period or a semi-colon. Use a comma plus a coordinating conjunction* (and, but, or, etc). Alternatively, use a comma plus a subordinating conjunction (after, although, as, because, before, even though, if, unless, when, while, etc). A slightly more elegant way is to use a semi-colon with a transition (also, as a result, consequently, instead, moreover, on the other hand etc).

E.g. 1:

Jenny prepared a salad she forgot to add tomatoes. (incorrect)

Jenny prepared a salad. She forgot to add tomatoes.

Jenny prepared a salad; she forgot to add tomatoes.

E.g. 2:

Tom enjoys tennis he prefers mixed doubles. (incorrect)

Tom enjoys tennis, and/but prefers mixed doubles.

E.g. 3:

Rachel and Megan love running Chloe doesn’t. (incorrect)

Although Rachel and Megan love running, Chloe doesn’t.

E.g. 4:

James thought the presentation went badly he was wrong. (incorrect)

James thought the presentation went badly; however, he was wrong.

Missing commas

When commas are omitted after introductory clause, phrase or word, the sentence can sound garbled and sometimes confuse the reader.

E.g. 1:

Before I could reply he put the phone down. (incorrect)

Before I could reply, he put the phone down. (correct)

E.g. 2:

If you want to get ahead get a hat. (incorrect)

If you want to get ahead, get a hat. (correct)

Commas missing from compound sentences

Compound sentences contain two clauses, each of which could stand alone and still make sense, but when joined together as one sentence, requires a coordinating conjunction*, preceded by a comma.

E.g. 1

The child opened the door and he ran away without being seen by his parents. (incorrect)

The child opened the door, and he ran away without being seen by his parents. (correct)

E.g. 2

The girl was very photogenic but her acting skills were limited. (incorrect)

The girl was very photogenic, but her acting skills were limited. (correct)

Superfluous commas

Just as missing commas can cause confusion, so can superfluous commas. These can also irritate the reader by interrupting the flow of the sentence.

Consider these examples, in all of which the comma is superfluous:

James knew at once, what his wife would say next.

The woman glanced at Jane, before making her way towards her.

The girl held her breath, as the car sped off along the road.

Michael had inside knowledge, because his father used work at the same factory.

The red coat lying on the floor, belongs to the girl with brown hair.

*A handy way to remember the seven coordinating conjunctions is to turn them into a mnemonic such as FANBOYS: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So

Homophones and Commonly Confused or Wrongly-Used Words

A homophone (or homonym) is a word that has a similar pronunciation to another word, but a completely different meaning. The spelling of the word can be the same, or different and these words often cause confusion. When the spelling is the same, these words can also be called homographs. When the spelling is different, they can also be called heterographs. Not all the words listed below are homophones, but they often cause confusion in writing:

Accept/Except

Accept is a verb meaning to receive.

E.g.

She accepted my invitation to dinner.

Except is a preposition, conjunction or verb, meaning exclude, omit, or leave out.

E.g.

I remembered everything on my list except for my passport.

As a conjunction, the word is often used immediately before a statement forming an exception to the one used previously.

E.g.

She told me the name of everyone present, except that she forgot to mention Tom was there.

As a verb, the word often has a more formal context specifying an exclusion from a group or category.

E.g.

The rules are straightforward, but there is one important exception to them.

Adverse/Averse

Adverse means unfavourable, and often relates to something beyond our control.

E.g.

Adverse weather conditions prevented us from going out that day.

Averse relates to attitudes or feelings of opposition regarding a subject.

E.g.

My father is not averse to a drink; he often enjoys a glass of wine with his meals.

Advice/Advise

Both words mean giving help, guidance, instruction, information etc. However advice is a noun

E.g.

The doctor’s advice was for him to lose weight.

Whereas advise is the verb:

E.g.

The doctor advised him to lose weight.

Affect/Effect

Affect is more often than not a verb meaning to have an influence on something; whereas effect is a noun relating to the consequence of an action or cause.

E.g.

Jane was deeply affected by the sad music, and unable to speak for some time.

The effect the sad music had on Jane became clear when she was unable to speak for some time.

(Tip: if you can substitute the word ‘alter’ or ‘altered’ in the sentence without changing its meaning, you know you need the word ‘affect’; if you can substitute the word ‘result’, you can be confident you need the word ‘effect’).

However, effect can also be used as a verb in formal contexts, meaning to achieve, execute or bring about something:

E.g.

The governor effected drastic changes to the prison policies.

Alot/A lot vs Allot

The word alot simply does not exist. It is sometimes confused in writing for ‘a lot’.

E.g.

There are a lot of ingredients in this recipe.

Allot means to allocate or apportion:

E.g.

The tutor will allot ten minutes to each student for his or her presentation.

Assure/Insure/Ensure

These three commonly confused verbs have different meanings.

To assure means to dispel all doubts by telling or promising someone something with certainty.

E.g.

I can assure you that Sarah was with me all afternoon.

Ensure means to guarantee something with certainty.

E.g.

I will ensure Michael arrives on time for his lesson tomorrow.

Insure means to secure or protect something (usually by taking out an insurance policy)

E.g.

Fortunately I remembered to insure the ring against loss or damage, so I will be fully compensated.

Breathe/Breath

Breathe (with a long ‘e’ sound) is a verb relating to the action of inhaling and exhaling, and breath (short ‘e’) is a noun that describes the air going in and out of the lungs.

E.g.

The midwife instructed the pregnant woman to breathe deeply through her contractions.

After running up five flights of stairs, Tom was short of breath and had to stop for a rest.

Between/Among

Between relates to the space (or thing) separating two objects, or the period separating two points in time.

E.g.

The bride and groom stood between both sets of parents for the photographs. And:

I plan to arrive at the theatre between six and seven p.m.

Among refers to being situated within a group of other things.

E.g.

I found the letter among a pile of other mail sitting on my desk. And:

Two children were among the victims of the traffic accident.

Cite/Site/Sight

Cite (verb) means to quote or to make formal mention of something or someone.

E.g.

You must remember to cite your sources at the end of your essay, using the Harvard style of referencing.

Site refers to a specific location, such as a tourist landmark, or a building site. Nowadays it is also often used as the shortened form of website.

E.g.

Westminster Abbey is a major tourist site in London and is situated close to other popular attractions, like the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, and Buckingham Palace.

Sight relates to vision, or eyesight.

E.g.

Everyone on the boat started to cheer when the famous statue came into sight. And:

I started wearing glasses when my sight began to fail.

Compliment/Complement

To pay a compliment is to say something nice about someone or something.

E.g.

I received many compliments about my new hairstyle.

Complement means to complete something. It can also relate to things fitting well together.

E.g.

We have a full complement of staff in this department, and are not looking to hire anyone new at the moment. And:

That cream jacket complements your brown skirt perfectly.

Diffuse/Defuse

The word defuse means literally to remove the fuse from a device, thereby preventing an explosion. You can therefore defuse a tense, dangerous or harmful situation.

E.g.

The unexploded bomb was successfully defused by the military specialist. And:

The teacher managed to defuse a potentially dangerous situation between the argumentative students.

Diffuse, on the other hand, means to scatter or spread across a wide area. As an adjective, it can also mean confused or lacking in clarity.

E.g.

The delicious smell of baking bread diffused every room in the house. And:

His diffuse and rambling speech weakened his argument considerably.

Discrete/Discreet

Discrete means on its own, separate, individual and distinct.

E.g.

The job application required three discrete referees, so I had to find three people who were completely unrelated.

Discrete means careful and reserved, especially in the way one speaks or acts. You can expect a discrete person to be circumspect and not draw attention to himself or what he knows.

E.g.

Jane is always discrete, which is why all her friends trust her and feel safe in confiding in her.

Elicit/Illicit

Elicit is a verb meaning to induce, or draw out a response or reaction.

E.g.

Despite being very funny, he could not elicit a smile from the unhappy child.

Illicit is an adjective meaning illegal, or against the law.

E.g.

The police caught him in possession of illicit substances, and he was sent to prison.

Farther/Further

Farther relates to actual or physical distances, while further relates to figurative or metaphorical distances. However, many people use the words interchangeably, with ‘further’ being used most frequently in both senses.

E.g.

The station is just a mile farther down the road. Or:

The teacher would allow no further questions and the exam started in silence.

Flaunt/Flout

These two verbs are often confused because they sound similar, but they have quite different meanings.

Flaunt means to show off or display something in an ostentatious way in order to draw attention.

E.g.

Sarah loves to flaunt her wealth by wearing designer clothes and expensive jewellery to work.

Flout is to show contempt for, or disregard rules or conventions.

E.g.

If you flout the school rules by refusing to wear the proper uniform, you will be suspended.

Its/It’s

The possessive noun its means ‘belonging to it’. It’s is a contraction of ‘it is’.

E.g.

The horse swished its tail from side to side to deter the flies. And:

It’s clear from your tone that you’re not happy with my decision.

Less or Fewer

Although these are not homophones, I have included them because they are frequently confused. Less should be used for uncountable nouns – e.g. information, luggage, money, news; whereas fewer is used for countable nouns – e.g. animals, cups, dollars, tables.

E.g.

I noticed Sarah had less luggage than me as we piled our suitcases into the taxi. Or:

There are fewer cups than saucers in the cupboard, suggesting some cups had been broken.

Lose/Loose

Lose is the verb, while loose is usually an adjective (though in rare circumstances it is used as a verb). To lose is to misplace something or not to be on the winning side.

E.g.

The child managed to lose a shoe while playing in the park. And:

If we don’t train harder, our team will lose the match again.

Loose means slack-fitting, or free.

E.g.

The dentist offered to remove the child’s loose tooth. And:

The cows are loose from the field again, and wandering all over the lane.

Peek/Peak/Pique

Peek can be a noun or a verb, and means to take a quick or furtive look at something.

E.g.

(noun) The child crept into the room and took a quick peek at the presents stacked under the tree.

(verb) The child peeked at the presents stacked under the tree.

Peak means the top of something, usually a mountain. It can be a noun, verb or adjective.

E.g.

(noun) The peak of the mountain was just visible through the morning haze.

(verb) He peaked in the final race, breaking his former record.

(adjective) Her long holiday restored her health to peak condition.

Pique can be a noun or a verb. As a noun it means irritation, resentment or bad temper.

E.g.

Jane could tolerate his attitude no longer, and left the party in a fit of pique.

As a verb, as well as feeling annoyed or resentful, it can also mean to stimulate or arouse interest or curiosity in something.

E.g.

He tried to pique my curiosity by dropping hints about the birthday surprise he planned.

Than/Then

We use ‘than’ for comparisons and ‘then’ to show time or sequencing.

E.g.

Tom is taller than Ben. And:

Ben entered the room first, then Tom followed two minutes later.

They’re/Their/There

They’re is the contracted form of ‘they are’.

E.g.

You can depend on the Bensons to arrive on time; they’re always punctual.

There is the possessive form of ‘they’.

E.g.

The guests left their outdoor coats in the cloakroom.

There refers to a place.

E.g.

You can see the building over there.

Tortuous/Torturous

Tortuous means meandering, or full of twists and turns.

E.g.

The tortuous route took in every little nook and cranny along the way.

Torturous relates to being tortured.

E.g.

He found the rigors of the boot camp too grim and torturous and had to leave on the second day.

Whose/Who’s

Whose is a pronoun of possession or belonging whereas who’s is the contracted form of ‘who is’.

E.g.

“Whose book is this?” the teacher asked. And:

“Who’s coming to the match with me?”

Who/Whom

Who and whom are both pronouns. Who refers to the subject of a sentence, whereas whom refers to the object of a verb/preposition.

E.g.

Who is that man standing by the door? And:

I’ve invited four people, only three of whom I actually know.

NB There is a simple tip that can help you remember whether to use who or whom in a sentence. Try substituting the pronouns ‘he’, ‘she’ or ‘they’ – you may well have to rephrase the sentence. If this sounds correct, use ‘who’. If substituting ‘him’, ‘her’ or ‘them’ sounds correct, then use ‘whom’.

Your/You’re

Your is an adjective meaning belonging to you.

E.g.

Your house is much larger than mine.

You’re is the contracted form of you are.

E.g.

You’re coming to my party, aren’t you?

Modifiers

As the word suggest, a modifier alters a sentence by providing it with extra, relevant information. It is used to add clarity, detail, explanation or emphasis, as well as making the sentence more interesting to the reader. If used incorrectly, however, modifiers can render the meaning unclear and confuse the reader. This happens with dangling or misplaced modifiers.

Dangling modifiers (also called dangling participles)

These make the subject of the modifying phrase unclear.

E.g. 1:

After waiting in the queue for two hours, the theatre doors finally opened to our relief.

This sentence fails to explain the subject of the participle waiting, and, in fact, sounds as if the theatre doors did the waiting. This can easily be corrected by adding a subject (usually with a verb) and bringing this closer to the modifying phrase:

After waiting in the queue for two hours, we were relieved when the theatre doors finally opened.

E.g. 2:

Entering the house, the smell of burning was immediately noticeable.

Since the subject of the phrase Entering the house cannot be the smell of burning, the modifier is left dangling. A subject needs to be included to remedy it, for example:

Entering the house, they immediately noticed the smell of burning.

E.g. 3:

At only two years of age, my parents took me to live abroad.

Because the age of two years relates to me and not my parents, this sentence needs to be rectified, and the simplest way is as follows:

When I was only two years of age, my parents took me to live abroad.

Misplaced modifiers

These cause confusion because, as the name suggests, the modifier is incorrectly placed in the sentence.

E.g.

John gulped down a hot cup of coffee before dashing off to catch his train.

This sentence suggests that it was the cup that was hot, not the coffee, and can easily be rectified for complete clarity by moving the modifying adjective next to the noun it is describing, thus:

John gulped down a cup of hot coffee before dashing off to catch his train.

Limiting modifiers

Modifiers such as almost, only, just, simply, merely, hardly, or nearly serve to impose limitations on another word in the sentence—usually the one directly after it. When these are misplaced—and, sadly, they often are—the meaning of the sentence can change completely.

E.g.

I have only one thing to say to you. (= I have one thing to say and nothing else)

Only I have one thing to say to you. (= No one else will say anything to you)

I have one thing to say to you only. (= I will say it to you and no one else)

For the sake of clarity, always remember to place the limiting modifier immediately before the word to which it relates.

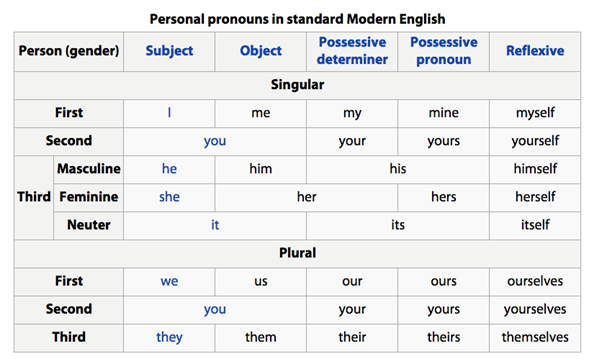

Pronoun Errors

Pronouns are noun substitutes, and errors occur when they do not agree in some way with the noun they are replacing. Words that are replaced by pronouns are called antecedents.

In all the following examples, the noun is underlined and the pronoun is in italics:

Mr Jones left his bicycle at home and walked to his place of work.

A singular noun must have a singular pronoun and a plural noun a plural pronoun.

E.g.

People had to find their own seats in the theatre.

The house stood on its own in the middle of the moor.

Everyone should have a black pen in his or her pencil case.

Uncountable nouns take singular pronouns and countable nouns plural.

E.g.

The furniture has now been put in its proper place.

The knives are in their correct drawer in the kitchen.

Money is the root of all evil, but, unfortunately, we need it for so many things.

Students must attend all their classes. Any student failing to do so, will receive a black mark against his or her name.

(Pronoun table courtesy of Wikipedia)

Split Infinitives

Everyone knows William Shatner’s famous example of a split infinitive from the opening of each episode of ‘Star Trek’: To boldly go where no man has gone before, but only consider the alternative and it becomes clear why it has endured. To go boldly where no man has gone before sounds weaker and less dramatic. Although language experts may not approve of split infinitives, there are cases for allowing them if they threaten to make a sentence clumsy or inelegant.

An infinitive, according to the Oxford English Dictionary is “The basic form of a verb, without an inflection binding it to a particular subject or tense.” This, in English, refers to the word ‘to’.

E.g.

to run, to work, to play, to hide, to live, to love etc

When the word ‘to’ is split from its verb by the insertion of other words, a ‘split infinitive’ occurs, hence: To boldly go…

In formal, or academic writing, it is advisable to avoid split infinitives, and in most cases, this is relatively easy to do:

E.g.

I was taught to never use split infinitives in formal essays. / I was taught never to use split infinitives in formal essays.

When turning right, it is important to clearly signal. / When turning right it is important to signal clearly.

I am able to skilfully apply the knowledge gained from my studies. / I am able to apply with skill the knowledge gained from my studies.

Subject-Verb Agreement

In sentences, subjects and verbs must agree with each other in number. When the subject of the sentence is singular, its verb must also be singular; when the subject of the sentence is plural, the verb must also be plural.

For example:

A crucial part of this hotel’s success have been the dedicated staff. (incorrect)

A crucial part of this hotel’s success has been the dedicated staff. (correct)

And

The two subjects she excelled in at school was French and English. (incorrect)

The two subjects she excelled in at school were French and English. (correct)

As long as you can find the right subject and verb in a sentence, you will be able to correct errors in subject-verb agreement easily.

E.g.

The list of wedding guests are/is on my computer.

Here the subject of the sentence is list (singular) so the verb (is) should also be singular.

Sentences with more than one singular subject, connected by either/or, or neither/nor also require a singular verb.

E.g.

My brother or sister is attending the ceremony.

Neither my brother nor sister is attending the ceremony.

Either my brother or sister is attending the ceremony.

When two or more subjects are connected by and, then a plural verb is needed as a general rule.

E.g.

Sarah and Mike are attending the ceremony.

The exception to this rule is when compound nouns form the subject of the sentence

E.g.

The bed and breakfast is closed for the winter months.

Another exception occurs when the subject relates to time, distance, sums of money etc., which are considered to make up one unit.

E.g.

Two hours is too long to wait in a queue

Ten miles is a long way to walk

Twenty dollars is too much to pay for that vase

But when a unit is broken up into sections or segments of the whole, using qualifiers like some, many, a lot, or a fraction such as a half or a quarter followed by the word of, the noun following the word of dictates whether the verb is singular or plural:

E.g.

Some of the house was destroyed by the fire.

Some of the houses were destroyed by fire.

Half of the cake has been eaten.

Half of the cakes have been eaten.

When it comes to collective nouns, such as family, group, team, committee etc., the singular verb is used to imply the group is one unit. However, there is slightly more flexibility here, depending on the writer’s/speaker’s purpose.

E.g.

His family all agree/agrees with him

Most of the group play/plays guitar

More useful helps and tips can be found on the Grammarly blog, as well as on Dictionary.com and Your Dictionary. This section, however, will continue to be updated regularly and if you have any questions concerning Grammar issues that you would like to have clarified, please feel free to let us know.

Why students should use our service

We hope you have found this grammar page helpful, but remember, as you tackle your writing assignments, our writing tutors are available to help every step along the way. We have highly qualified writing tutors who can help with any level of assignment and assist with any grammar issue you encounter from high school onward.

24HourAnswers has been helping students as a US-based online tutoring business since 2005, and our tutors have worked tirelessly to provide students with the best support possible. We are proud to be A+ rated by the Better Business Bureau (BBB), a testament to the quality support delivered by our tutors every day. We have the highest quality experts, with tutors from academia and numerous esteemed institutions.

To fulfill our tutoring mission of online education, our college homework help and online tutoring centers are standing by 24/7, ready to assist college students who need homework help with all aspects of grammar. Our languages and writing tutors can help with all your projects, large or small, and we challenge you to find better online tutoring in grammar anywhere.

College Grammar Homework Help

Since we have tutors in all Grammar related topics, we can provide a range of different services. Our online Grammar tutors will:

- Provide specific insight for homework assignments.

- Review broad conceptual ideas and chapters.

- Simplify complex topics into digestible pieces of information.

- Answer any Grammar related questions.

- Tailor instruction to fit your style of learning.

With these capabilities, our college Grammar tutors will give you the tools you need to gain a comprehensive knowledge of Grammar you can use in future courses.

24HourAnswers Online Grammar Tutors

Our tutors are just as dedicated to your success in class as you are, so they are available around the clock to assist you with questions, homework, exam preparation and any Grammar related assignments you need extra help completing.

In addition to gaining access to highly qualified tutors, you'll also strengthen your confidence level in the classroom when you work with us. This newfound confidence will allow you to apply your Grammar knowledge in future courses and keep your education progressing smoothly.

Because our college Grammar tutors are fully remote, seeking their help is easy. Rather than spend valuable time trying to find a local Grammar tutor you can trust, just call on our tutors whenever you need them without any conflicting schedules getting in the way.